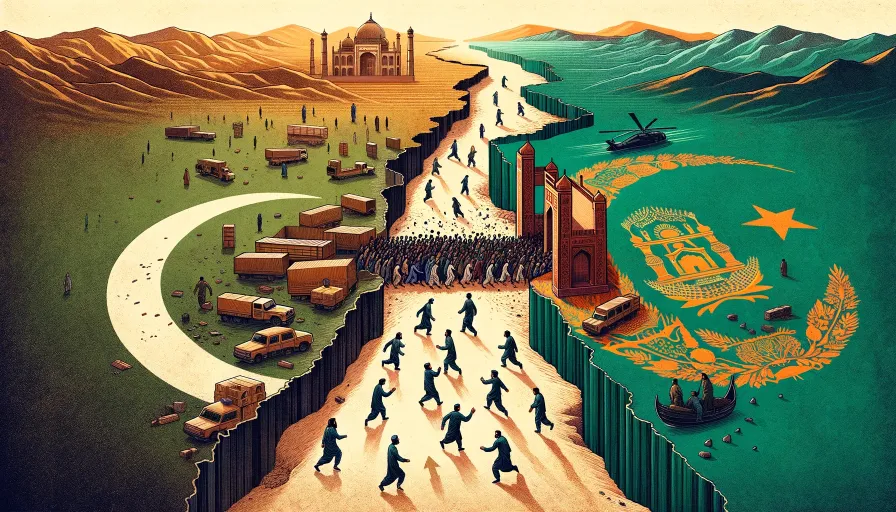

A humanitarian crisis is unfolding as hundreds of thousands of Afghans have been forced to leave Pakistan in recent weeks as authorities pursue civilians they say are in the country illegally, going door-to-door to check documentation. While the government has allowed for an extension to the original deadline of Nov. 1, many Afghan civilians are caught in this crisis without knowing what to do.

This policy impacts over a million Afghans, a population Islamabad accuses of being involved in militant activities and crimes, allegations that the Kabul administration firmly denies.

In October, Pakistan’s government, led by caretaker Prime Minister Anwaar-ul-Haq Kakar, issued a stern directive to all undocumented foreigners, giving them until November 1 to leave the country voluntarily. This ultimatum was underscored with the threat of arrest and deportation for non-compliance.

Since the initial announcement, over 250,000 Afghan nationals have voluntarily returned to Afghanistan, out of fear of retribution by Pakistan.

The Afghan Taliban government, however, has expressed strong opposition to this deportation policy, urging the Pakistani authorities to reconsider. Simultaneously, the United Nations and various global human rights organizations have raised alarms about the potential humanitarian crisis this is causing. They highlight concerns regarding retribution and abuses that returnees might face under the Taliban regime.

The Taliban’s return to power in Afghanistan in August 2021 was the culmination of a series of events and factors spanning several decades. Originally emerging in the early 1990s from mujahideen fighters who had resisted the Soviet occupation, the Taliban swiftly gained control over Afghanistan, establishing a regime known for its strict interpretation of Islamic law. This regime was toppled by a U.S.-led military invasion in 2001 following the September 11 attacks, as the Taliban were harboring Al-Qaeda leaders, including Osama bin Laden. However, rather than disappearing, the Taliban transitioned into an insurgent force, engaging in guerilla warfare against the U.S.-led coalition and the Afghan government. Over the years, they regained strength and control in rural areas of Afghanistan.

The history of hostilities between Pakistan and Afghanistan is complex and dates back to the early 20th century. The primary source of tension has been the Durand Line, a border established in 1893 by the British, which Afghanistan has historically not recognized. This disagreement has led to numerous border skirmishes and diplomatic disputes. After Pakistan’s independence in 1947, relations remained strained, with Afghanistan being the only country to vote against Pakistan’s admission to the United Nations.

The situation escalated during the Cold War, particularly after the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979. Pakistan, with support from the United States, played a key role in supporting Afghan mujahideen fighters against Soviet forces. This period saw an influx of Afghan refugees into Pakistan, further complicating relations. After the Soviet withdrawal in 1989 and the subsequent Afghan civil war, Pakistan was influential in the rise of the Taliban, which further strained relations as Afghanistan accused Pakistan of interference.

In the post-9/11 era, with the U.S. invasion of Afghanistan and the fall of the Taliban, tensions persisted. Afghanistan accused Pakistan of providing safe havens for Taliban insurgents, while Pakistan accused Afghanistan of harboring anti-Pakistan militants. These accusations led to frequent diplomatic clashes and border tensions.

The situation took a decisive turn with the gradual withdrawal of U.S. and NATO forces. The February 2020 Doha agreement between the U.S. and the Taliban, which stipulated the withdrawal of all foreign forces in exchange for security assurances, accelerated this process. In the months that followed, the Taliban rapidly expanded their control. The Afghan National Defense and Security Forces, despite substantial support from the U.S. and its allies, struggled to counter the Taliban’s advances, plagued by issues such as low morale and logistical challenges. This led to a rapid and largely unopposed Taliban advance, culminating in the fall of Kabul on August 15, 2021. The Afghan government, led by President Ashraf Ghani, collapsed, with Ghani fleeing the country, and the Taliban effectively took control.

Amnesty International has been critical of Pakistan’s actions. The organization’s deputy regional director for South Asia campaigns, Livia Saccardi, called for an immediate halt to detentions and deportations. She emphasized the principle of non-refoulement under international law, warning that continued deportations could deprive vulnerable Afghans of essential safety, educational opportunities, and means to earn a living.

“Pakistan’s announced deadline for Afghans to return has led to detentions, beatings, and extortion, leaving thousands of Afghans in fear over their future,” said Fereshta Abbasi, Afghanistan researcher at Human Rights Watch (HRW). “The situation in Afghanistan remains dangerous for many who fled, and deportation will expose them to significant security risks, including threats to their lives and well-being.”

According to HRW, “These deportations violate Pakistan’s obligations as a party to the UN Convention Against Torture and under the customary international law principle of nonrefoulment – not to forcibly return people to countries where they face a clear risk of torture or other persecution. Refoulement occurs not only when a refugee is directly rejected or expelled, but also when indirect pressure is so intense that it leads people to believe they have no option but to return to a country where they face a serious risk of harm.”

Without an immediate solution, Afghani citizens stuck in Pakistan may soon be deprived completely of their rights and subject to human rights abuses. The world must step up efforts to pressure Pakistan to back away from this inhumane policy and find an alternative solution to the problem without harming innocents.