After the initial invasion failed and Russia was forced to retreat from northeastern Ukraine at the end of March and April 2022, Russia changed its strategy. Fast mechanized maneuvers were out, attrition fighting with overwhelming artillery advantage was in.

But even that approach failed Russia during the summer of 2022 with the arrival of the HIMARS rocket system. Western and Ukrainian intelligence, combined with the HIMARS missile’s deadly range of 84 km, allowed Ukraine to prevent Russia from supplying its artillery with sufficient shells to effectively dislodge the Ukrainian defenders.

Despite the well-known Russian artillery advantage during the spring and summer of 2022, artillery shells weren’t the only thing that Russia expended during its offensive in large numbers. Russian also expended extensive manpower capturing that territory. Already during that time, it was rare to find able bodied men in the Luhansk and Donetsk people’s republics [DNR & LNR]. Russian authorities declared a general mobilization in the Russian-affiliated separatist states several days before the war even began because after six months of fighting, the manpower resource of those republics was spent.

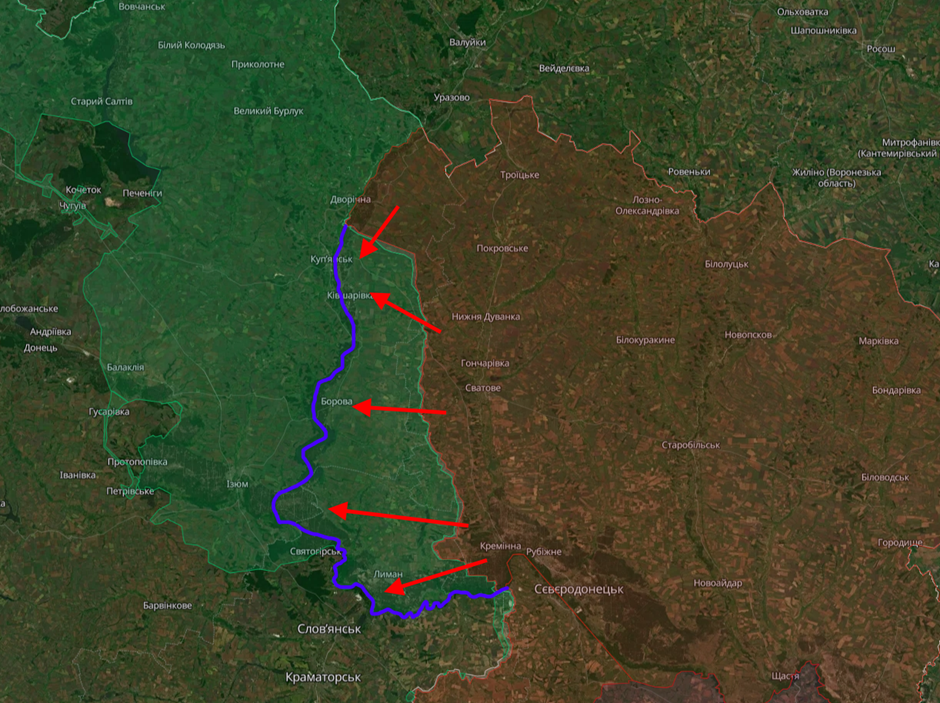

From the end of August to November, Ukraine conducted its own series of offensives, first in the Kherson oblast, trying to recapture the city of Kherson. Because of manpower shortages and the need to send reinforcements to the Kherson front, Ukrainian intelligence discovered that the frontline in the Kharkiv area was lightly manned and could be overrun. After the fighting died down in October in Ukraine’s north, and as the frontline re-solidified, Ukraine managed to retake Kherson after forcing the Russians to retreat.

Impacts on the frontline

Although both the Kharkiv and Kherson offensives proved successful, the Kremlin declared a partial mobilization to resolve its manpower shortage on the front.

Considering the significant shortening of the frontline and Russian mobilization, the density of Russian soldiers on the frontline rose by about 2.5 times solving the problem that led to the successful Ukrainian campaign in Kharkiv.

![[Area regained by Ukraine during August – November 2022 is in blue]](https://newsentinel.org/wp-content/uploads/image-1.png)

During the winter of 2023, we witnessed a general Russian offensive localized to specific areas only. This, combined with Russian military bloggers’ statements, gave us the ability to understand Russia’s long-term plan.

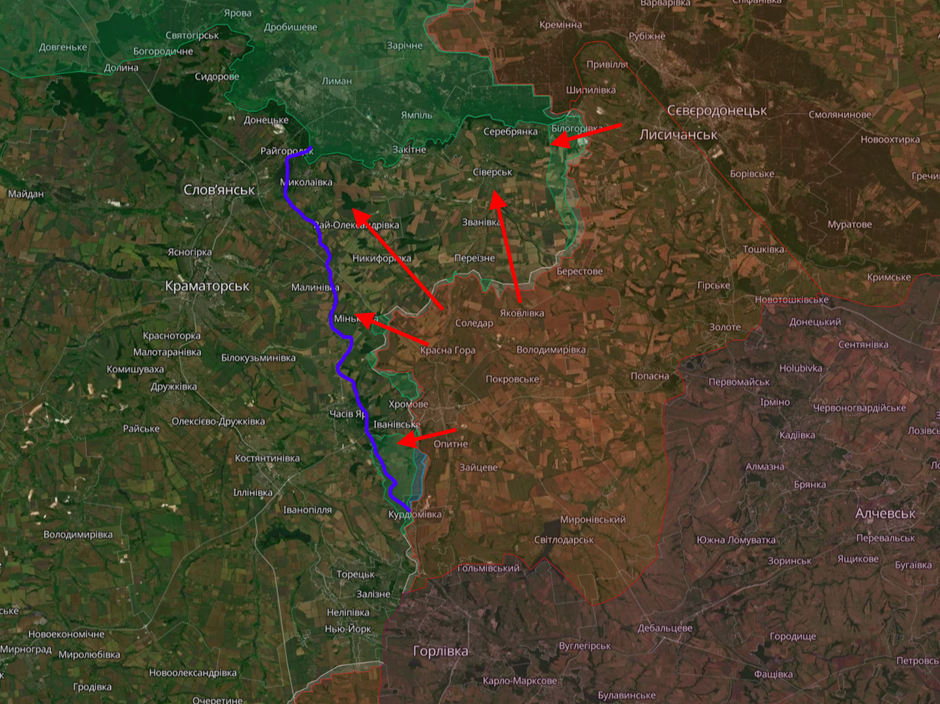

Much of the Russian offensive potential was used in the north, trying to push Ukraine back to the Oskil and Seversky Donets rivers behind which the Russian army could hold good defensive positions. We know this was the Russian goal due to statements published by the official Russian media. However, the Russian offensive went nowhere and they failed to significantly advance.

The Bakhmut front

On the Bakhmut [or northern Donetsk] front, the Russians also tried to reach good natural borders to facilitate easier defense. Although this area doesn’t have any good natural barriers such as the rivers mentioned previously, it has an artificial barrier – a large water canal meant to supply the cities further south. Anchoring themselves on this natural landscape would make defense very easy.

In contrast with the Luhansk effort that resulted in no movement of the front, the Bakhmut effort led to the fall of the city itself, after almost 10 months of fighting. But the brutal battle of Bakhmut sapped the Russian army of resources and strength, which caused it to cancel any further offensive action in the area.

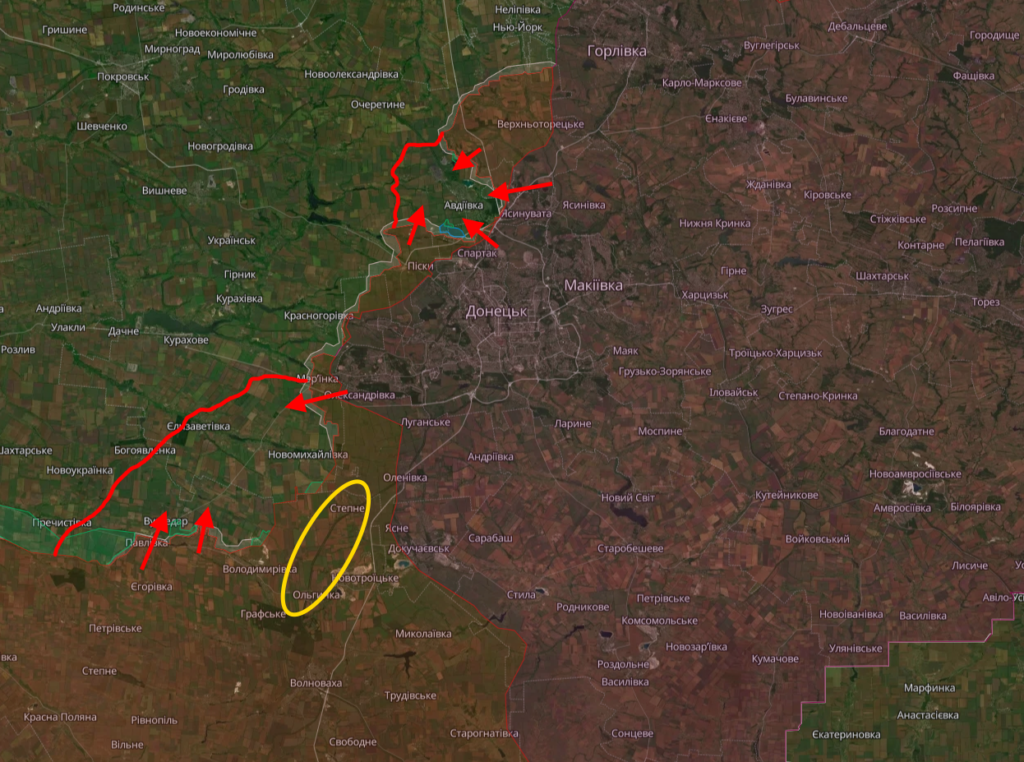

Avdiivka and Vuhledar front

The last Russian effort was made on the southern Donetsk front; its aim was to capture the fortress towns of Avdiivka and Vuhledar. In contrast to the previous two efforts of the offensive, this one had to do with improving logistics for a large part of the army. The city of Donetsk itself is a huge Russian logistics hub, and Ukrainian artillery can reach targets in the city. Vuhledar is a small mining town that controls the local heights from where soldiers can target the Donetsk – Volnovakha railroad – a critical logistical route that the Russians currently can’t use.

Removing the Ukrainians from Avdiivka and Vuhledar would make logistics for the entire southern front much easier for the Russian army. But here also the Russian army failed at its objective. Russian frontline reporters describe the attacks on Avdiivka as “meat assaults without result” and the battle of Vuhledar was probably the most one-sided major engagement during this war. Several Russian brigades lost their combat effectiveness trying to take the town, which was defended at the time by just one Ukrainian brigade.

In summary, we see Russia’s aims to entrench itself in good defensive positions and improve its logistical situation in the south. We can deduce from this that Russia aims for a long war, aiming to outlast Ukraine and wait for Western support to waver. The better defensive positions aim to free manpower to prevent another mobilization wave. Russia believes it can win the war with volunteer contracts. In order to win, the West must intensify military aid to Ukraine and make it crystal clear that the support for Ukraine will last until victory.